Discussion over the Ebola outbreak in the U.S. has gotten into some pretty contentious territory lately.

ALEX WAGNER VIA MSNBC: "I mean, it's not even thinly-veiled racism at this point."

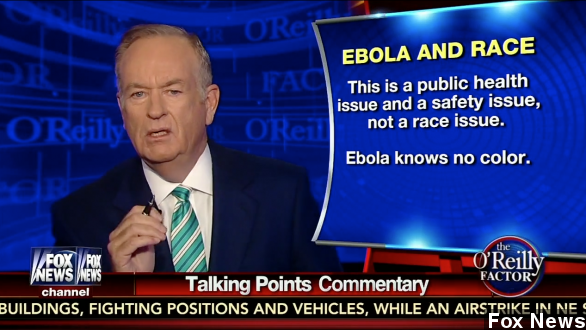

BILL O'REILY VIA FOX NEWS: "This is a public health issue and a safety issue, not a race issue."

MELISSA HARRIS-PERRY VIA MSNBC: "The only person to have died in this country of Ebola is a West African black man."

The argument here is that black victims of the disease, which of course originated in West Africa, have been ignored — and that Africans are being discriminated against more broadly because of the disease's origins.

This debate over race and Ebola has been going on since before the U.S. even saw its first death from Ebola. In August, Newsweek faced backlash over the cover of one of its magazines, which featured a chimp and warned that African bushmeat could be a "back door for Ebola."

There have also been cases where students from Africa attempting to enroll in colleges have been denied due to new restrictions blocking applications from international students from countries stricken with Ebola.

And perhaps one of the more overt cases would be the assertion that the U.S.'s first Ebola death, Thomas Eric Duncan, was initially denied treatment at the hospital because he was West African.

JOHN WILEY PRICE VIA KTVT:"If a person who looks like me shows up without any insurance, they don't get the same treatment."

So what makes the discourse surrounding Ebola so different from, say, the SARS outbreak in 2003?

A Jezebel writer says this habit of "us versus them" is as old as European colonialism, with an emphasis on cleanliness eventually transforming into a social stigma against people from places seen to be unclean. (Video via Al Jazeera)

In July Slate wrote that stigmatizing those from foreign countries over disease in the U.S. is nothing new. In 1832 there were fears Irish immigrants would bring cholera. Then Chinese for the bubonic plague. And eventually Italians over polio.

An op-ed for The Guardian explains the result of the viewpoint like this: "Ebola now functions in popular discourse as a not-so-subtle, almost completely rhetorical stand-in for any combination of 'African-ness', 'blackness', 'foreign-ness' and 'infestation' — a nebulous but powerful threat, poised to ruin the perceived purity of western borders."

Proponents for measures like travel bans or tightening up border security say it's in the country's best interest — to eliminate as much of the chance of Ebola entering the U.S. as possible.

But the United Nations, for one, has cautioned against such steps, which it says are counterproductive.

The U.N.'s newly appointed high commissioner for human rights warned on Thursday that: "We must also beware of 'us' and 'them,' a mentality that locks people into rigid identity groups and reduces all Africans ... to a stereotype."